Here’s a cliché.

Describe yourself in three words.

We’re asked this question countless times throughout our lives for essays, interviews, and profiles with the ultimate goal being to consolidate and prioritize our best attributes.

Here’s a harder question.

Describe yourself in one word.

Harder.

Describe yourself in one image.

Logos.

With the creation of every new brand comes the necessity to create a visual representation of what you do, what you value, and what you’re going to do to make your voice heard in an over crowded market.

Starting March 1, 2016, The Metropolitan Museum of Art officially and completely changed its infamous “M” design to what’s thought to be an innovative and refreshing option. While David Brodsky, museum chairman, believes “its time for the Met to move forward”, numerous people have spoken out against the decision to rebrand.

The first design, seen 1971, has become a recognizable symbol for the museum for more reasons than just its appearance. Supporters and fans of The Met have created and connected to the various associations of the original work. Speculations include the design being based on a woodcut by Leonardo da Vinci’s teacher Luca Pacioli, a reference to a composition by Rafael, a representation of the museum’s architectural layout, or even a depiction of medieval manuscripts. The original design screams art history. It’s complex yet paradoxically simple composition of geometrical shapes and lines created layers of association and interest for art enthusiasts.

However, for those wishing to pursue other objectives for the museum, this same characteristic of complexity was posed as a potential turn off for visitors. Wishing to emphasize the theme of connectivity, The Met decided to invest in revisiting its visual identity. Their main goal involved overarching objectives of reach and relevance. Aiming to reduce the overwhelming nature of the 5000+ years of work within their walls, the new logo is intended to convey community and accessibility through the connected format of each letter. By choosing a font that’s “classical and modern”, the design is also envisioned to reference the museum’s past while still looking to the future.

Well, let’s here what the public thinks.

“The whole ensemble looks like a red double-decker bus that has stopped short, shoving the passengers into each other’s backs.” –Justin Davidson, Vulture.com

Ouch.

Criticisms of the new graphic identity involve everything from the font, the color, the layout, and the objective. The polarizing opinions have many weighing in their own “artistic” take. Contrasting the intention of The Met’s forward thinking approach, some blame the flop on the poor typography and believe it to be dated. Others hold the belief that a “museum shouldn’t try to be fashionable”. They don’t want The Met to disassociate itself from its most prominent attribute and service of providing and exemplifying history. The outrage was also posed to be stimulated by The Met’s earlier decision to discontinue their infamous metal admissions buttons to be replaced with a simple and economic sticker in 2013.

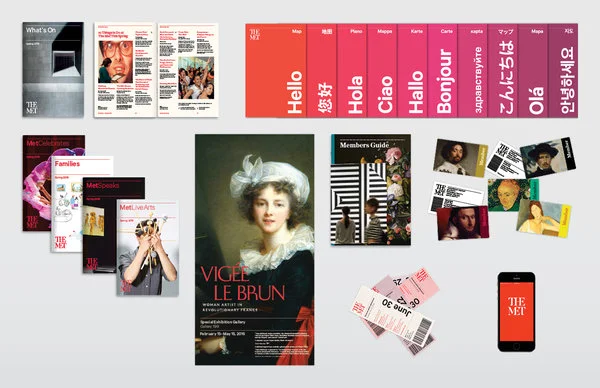

New advertising material

While brands always aim to be relevant, the decision to change things up always straddles a fine line between gaining new ground and loosing core foundation. Seth Godin, author of The Big Moo, included the advice that “a remarkable company doesn’t require spending tens of thousands or tens of millions on ‘reinvention’.”Sometimes there is a need for change, but Seth also offers that “customers sometimes love the simple stuff”.

Millions of dollars are spent to create this bundle of shapes and colors. However, the ability to create associations and evoke responses from just those few shapes and colors is a masterful art. The harmonious composition of a strong design aesthetic with an equally strong exemplification of the brand’s mission and product proves to be the hardest balance to capture.

With every art comes critique and criticism.